2 weeks ago I spent a bit of time talking about why you can still train while you’re injured and then last week defended the idea that injuries can actually be an opportunity to improve while on the the mend. That still doesn’t answer the main question I get at ASR:

“How long with this take to go away? When can I go back to CrossFit/running/swimming/throwing…etc.?”

A key part of my process is helping you understand their injury, and to work with you to get you back to whatever activity it is, without symptoms, as soon as possible.

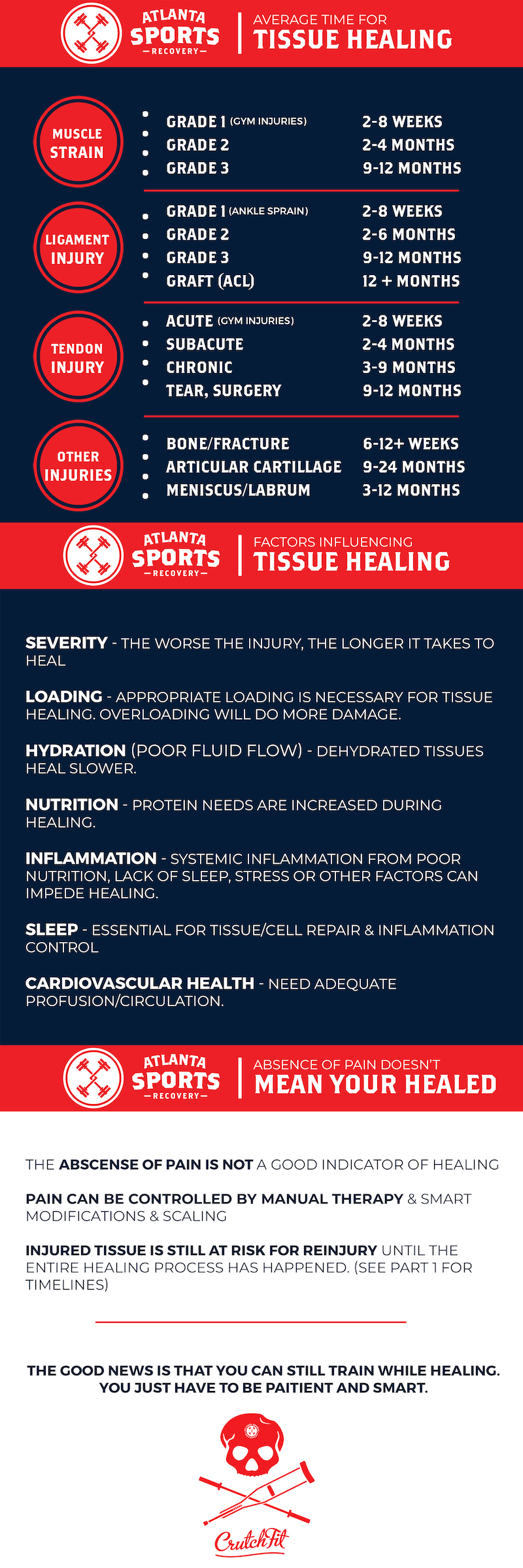

While the manual therapy techniques I employ can often rapidly eliminate pain and allow a resumption of activity, they can only speed human biology so much. When an injury occurs, there is often real irritation or damage to a structure, and this takes time to repair and remodel. Different tissues have different structures and varying degrees of blood flow, and therefore heal at different rates. Likewise, the severity of an injury will definitely affect healing time as well.

So, we find it helpful to discuss average healing times with many of our patients. This can give an expectation for how long an injury will take to truly heal. We created an infographic for many of the most common types of orthopedic injuries. Sources are listed below for the research geeks out there.

Just a caveat:

But what about pain?

In the first several visits with our new patients, we often place a focus on getting symptoms under control. Usually, this means reducing pain. In many cases, we can resolve or drastically reduce pain in just several focused sessions. However, the absence of pain does not mean that the injury is healed! We’re unfortunately not miracle workers, and cannot change human biology. We can only optimize. Until the tissue is fully remodeled, it will still be at risk of re-injury, even if pain is generally low.

A good example is plantar faciitis . This is a common injury that we see in runners who have pain in the bottom of their foot. I can usually eliminate 70-90% of pain in one visit using manual therapy and some biomechanics adjustments to how an athlete runs, stands or squats. But, this does NOT mean that I caused the irritated bottom of the foot to heal in 60 minutes. It’s simply been desensitized, like taking an addition free pain killer. In chronic cases, it may take 2-12 months for complete resolution of the injury. This does not mean 2-12 months of constant pain. It does mean 2-12 months of careful attention to symptoms, targeted exercise, a gradual re-exposure to loading, and dealing with possible recurrences of symptoms quickly.

Until the tissue is actually healed, it will be at increased risk of re-injury. Because I don’t have an imaging machine at my disposal I cannot tell when this has occurred, the general rule is that you’re not truly “out of the woods” until symptoms have been relatively quiet for multiple months with full activity.

Likewise, the presence of pain does not necessarily indicate significant tissue damage. (A quick example is a paper cut: It briefly hurts like crazy, but there’s not really much tissue damage.) After an injury, the nervous system remains sensitive to inputs in and round that area of the body. It becomes “protective” of the injured area, and pain is the nervous system’s alarm system. This especially true of areas that have been injured repeatedly, such as the bottom of the foot, the knees, or the lower back. When this happens, an introduction of a new stimulus, or a minor strain or tweak, can feel incredibly painful or sensitive. These occurrences are also common, indeed expected to some extent, as patients return to activity after an injury. In the absence of some new trauma, it’s important to not panic, calm symptoms down, and then proceed on with the rehabilitation process.

–

How did I get these timelines?

PubMed and our textbooks were used to come up with the most evidence-based estimates possible. If you have better information, please let us know! Credit must also go to Dr. Caleb Burgess, as one of his recent Instagram posts was the inspiration for this article. Here’s a list of sources:

Muscle Strains:

- MR observations of long-term musculotendon remodeling following a hamstring strain injury

- Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation, 2nd Edition by Brotzman and Wilk

Ligament Sprains:

- Ligament Injury and Healing: An Overview of Current Clinical Concepts

- Ligament Healing: A Review of Some Current Clinical and Experimental Concepts

- Ankle Ligament Healing After an Acute Ankle Sprain: An Evidence-Based Approach

- Nonoperative treatment of Grade II and III sprains of the lateral ligament compartment of the knee

Tendons:

- Painful, overuse tendon conditions have a non-inflammatory pathology

- Tendinopathy: Why the Difference Between Tendinitis and Tendinosis Matter

- Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation, 2nd Edition by Brotzman and Wilk

Articular Cartilage, Meniscus, and Labrum