All the training strategies are built around that principle of supercompensation.

The essence of the concept is simple.

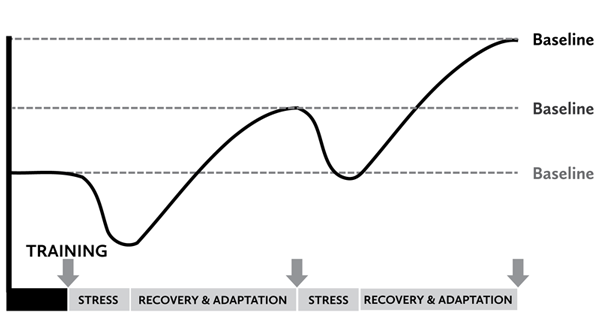

You are at a specific fitness level. Then you train, and your fitness temporarily decreases. Then you recover, your body adapts to the initial stress input, and you can tolerate more stress (i.e., do more) than before, making you fitter.

Unfortunately, the window of time in which you are more fit, called the window of supercompensation, is temporary.

If you train again with a slightly higher stress input (i.e., more weight, faster sprint) in said magical window of time, you start the whole cycle over. The stress will cause tissue damage; you will recover and heal and then be slightly fitter than before.

Doing this over and over again over time is how you progress from one athletic point to another.

Think of it as compounding interest for your fitness.

So basically, get a good training program. Do it consistently. Change the program every 12-16 weeks, and you will accomplish your training goals.

However, there is one very important and often overlooked detail in this equation. THE RECOVERY.

If you do not recover from the training input, the magical window of time, you are a superhuman version of your previous self NEVER HAPPENS.

If you attempt to train again at a heavier weight, run a longer distance, or faster pace, you will either fail at it or leverage your body in ways it is not meant to be leveraged to get the work done, which will eventually cause an injury.

If you do not recover from the training stimulus, it is impossible to become fitter, train harder, or become the athlete you want to be.

The moral here is that if you are going to train, you have to place equal importance on recovery. If you don’t, the effects of your training inputs are either blunted or are rendered worthless.